When will Australia's drought break?

For drought-busting rains, Australia might just have to wait for the tropical oceans to serve up some moisture, new research from Dr Andrew King

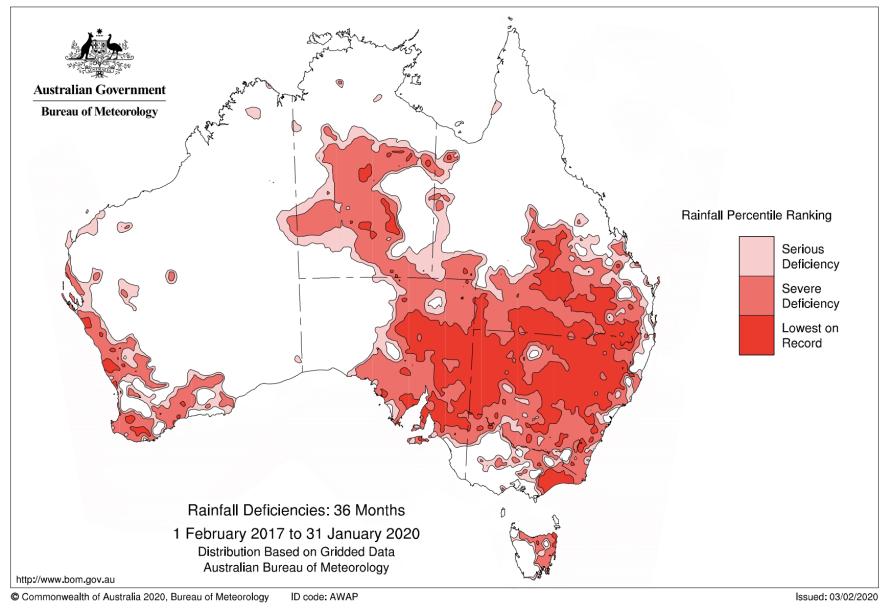

While some helpful rains have recently damped fire grounds and given our farmers something to cheer about, much of the southeast of Australia remains in severe drought.

In mid-2016, the last heavy winter rains fell over eastern Australia but, since then, dry conditions have dominated and a drought has developed that is among the worst on record, particularly in parts of New South Wales.

Australia is no stranger to droughts, but the current one still stands out when looking at the rainfall observations over the past 120 years.

The Murray-Darling Basin, a vital region for Australian agriculture, has not experienced a wetter than normal season since spring 2016. This drought has been marked by three consecutive extremely dry winters, all of which rank in the driest 10 per cent of winters.

Despite the recent drought, there is no strong trend towards drier conditions over most of the Murray Darling basin since 1900 (there is some evidence of drying in the extreme south of the basin).

In fact, historically we have seen many dry periods, like the 1930s and 1940s and the early 2000s, interspersed with wetter periods, such as in the 1950s, 1970s and the early 2010s.

The Murray-Darling Basin experiences high rainfall variability, with decade-long droughts common since observations began.

There has been much discussion about what’s causing the current drought and whether human-caused climate change is to blame.

In our new study we have explored Australian droughts through a different lens in order to understand what conditions are needed to break the drought?

The role of the Pacific and Indian Oceans

As many people already know, the Pacific Ocean affects Australian climate with El Niño events associated with drier weather and La Niña conditions associated with wetter weather over eastern Australia.

The Indian Ocean is also important and the Indian Ocean Dipole modulates our winter and springtime rainfall.

But, in 2017 and 2018 when the current drought started to take hold, we didn’t experience an El Niño or strongly positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) event.

Rather, conditions in the Pacific and Indian Oceans were near neutral with little to suggest we should have a drought developing.

So, why are we in a severe prolonged drought?

In our study, we propose that rather than focussing on what’s causing the dry conditions, we should investigate why it’s been such a long time since we had prolonged wet weather instead.

Australia is the driest inhabited continent on Earth and as such we normally experience fairly dry conditions over southern Australia.

For large areas of the continent to experience persistent widespread heavy rainfall, it helps if the oceans near Australia to our northwest and northeast are unusually warm.

For the southeast of Australia in particular, La Niña or negative IOD events provide the atmosphere with suitable conditions for persistent and widespread rainfall to occur. Neither La Niña or a negative IOD guarantee heavy rainfall, but they do increase the chances.

The problem is we haven’t had either a La Niña or negative IOD event since winter 2016.

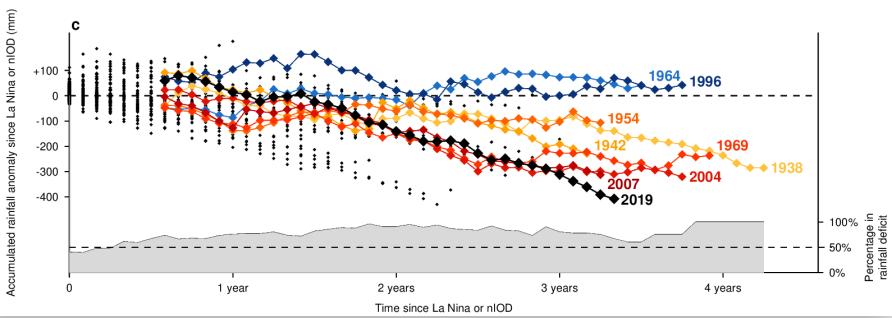

So, what does this graph mean?

The longer each line continues before stopping, the longer the time since a La Niña or negative IOD event.

The lower the lines travel, the less rainfall was received in the Murray Darling basin during this period.

This lets us compare the current drought to previous droughts.

Many of Australia’s droughts are characterised by long periods without either a La Niña or a negative IOD event occurring. This includes two periods of more than three years each during the Second World War drought and the Millennium drought when no La Niña nor a negative IOD event occurred.

During the current drought we see that the rainfall deficit accumulates for several years almost identically to periods of the Millennium drought, but then the deficit increases strongly in late 2019 when we had a strongly positive IOD.

What about the effects of climate change?

Clearly year-to-year variability in the Pacific and Indian Oceans is extremely important for determining if we are in drought in southeast Australia, with La Niña and negative IOD events helping to break droughts.

Changes in El Nino, La Nina or the IOD can change the likelihood of rainfall over Australia and so an important question is whether La Niña and negative IOD events will change in the future as the climate continues to warm.

So far, it’s tricky to tell.

There is some evidence that La Niña events will become more extreme and that negative IOD events will become less common.

Unfortunately, we can’t be sure how the ocean patterns that increase the chances of drought-breaking rains to Australia will change under continued global warming.

What is clear is that there is a risk that they will change and strongly affect our rainfall.

When will this drought break?

This is a hard question to answer.

While recent rains have been helpful, we’ve developed a long-term rainfall deficit in the Murray-Darling Basin and elsewhere that will be hard to recover from without either a La Niña or negative IOD event.

The most recent seasonal forecasts don’t predict either a negative IOD or La Niña event forming, but accurate forecasts are difficult at this time of year.

For now, we just have to hope conditions become more favourable in the coming months.

AUTHORS

Dr Andrew King is a Climate Extremes Research Fellow and a convenor of MSSI's Climate Transformations research cluster, at the University of Melbourne.

also authored by Dr Anna Ukkola, Dr Benjamin Henley, Dr Josephine Brown and Professor Andy Pitman

First published on in Science Matters

Banner: Getty Images

![]()